Herbert Lotz

The following oral history is the result of a recorded interview with Herbert A. Lotz conducted by Katie C. Doyle on May 2, 2023. This interview is part of the Rick Dillingham retrospective “To Make, Unmake, and Make Again” at the New Mexico Museum of Art.

Transcript:

Q: Hi, my name is Katie Doyle. I am the assistant curator at the New Mexico Museum of Art here on the [Santa Fe] Plaza. I am sitting here with Herbert [A.] Lotz, photographer and friend of Rick Dillingham. We will be recording an oral history for the Rick Dillingham retrospective exhibition “To Make, Unmake, and Make Again”. This oral history will go into the digital archive belonging to the New Mexico Museum of Art and will be held in perpetuity for scholarly research and posterity and record. It is 2:05 p.m. on Tuesday, the 2nd of May. We’re down in the basement in Merry Scully’s former office and we’ll probably dive right in. The first question on our interview is, “When and how did you meet Rick Dillingham?”

Lotz: I thought about that. Rick died in ‘94. It’s now thirty years later. I’ve tried to remember when we met and I don’t know, quite honestly, if it was when he was in college down at UNM [University of New Mexico] or when he came back from Claremont [College]. I’m not sure, quite honestly, I can’t pull that out of my memory. What I wrote down was we were probably introduced through the gay community here in Santa Fe, and that would have been when he probably first moved here. The community was small, very connected. We had a local bar that we all went to called the Senate Lounge. That used to be primarily for the legislature when they were doing the meetings, and then somehow it became more popular with the gay community. The gay community took it over, so I know that Rick and I would have hung out there. [Pause] Yes. When did he show up here? I’m not sure.

We might have also gotten connected through—I was working for the school at the time. It was called the School of American Research. I was documenting a lot of the work that they had in their archives. I believe he worked with them at some point. I also worked with a woman named Vicki Laszlo [Victoria Laszlo], and she would put pots back together. I think she worked for the School for American Research as well. Do you know Vicki Laszlo?—okay. There was a connection between Vicki, I think, and Rick and myself and the school. That was also part of how that happened. I also wrote down, being a photographer and photographing artwork, that’s what I did. There were probably a few of us photographers in town.

Rick and I connected very early about photographing his work, and he liked the way that I approached his work. I had [photographed] a lot of the Native American pottery, and so I was fairly good, I think, at lighting around objects like that to show their dimension, to keep them in perspective. I think he appreciated that very much. I did a book with Richard [L.] Spivey about my time with Maria Martinez working with all that black pottery. That can be very difficult to photograph. These are the old days when you weren’t using electronic imaging, so you had to work with lighting in a very controlled way. Anyway, Rick appreciated that very much. Very quickly I became his photographer and photographed all of his work. [Pause]

Q: When thinking about the relationship that you had with with Rick, how would you describe the nature of your relationship, aside from the business aspect of photographing the work? Were you friends?

Lotz: Yes, we were friends. We socialized. Rick had a great sense of humor. I like to think that I have a great sense of humor. [Laughter] Our times together was always very enjoyable. Yes, we worked together, but there was always humor in the relationship. I think there was affection for each other. We were never romantically involved. But I loved him very much. He had a very rich foundation of friendships and acquaintances and businesses that he worked with here. He was not a very singular person. He had a lot of relationships. A lot of people that I never met, never knew. He was well respected by pretty much everybody that worked with him. I wrote down here that we became very close friends.

We did do books together. If he wanted to work on a book for one reason or another, we would start working on that. That involved the friendship. It also involved what he was trying to do. Having shot many books, I could do that for him. I could provide the material, the visual material that he needed for these books. Is one of them Fourteen Families [in Pueblo Pottery]? I remember the books that we did together. I can’t get [the titles] right off the top of my head, but they’re very beautiful books. Also we danced together. I loved country Western dancing because I was a cowboy then. Yes. You may not know this about me [laughter]. I worked at a horse barn for seventeen years. I had two horses. I was a board—is this about me or about Rick?

Q: It’s about Rick.

Lotz: Okay. [Laughs]

Q: Well, we’ll have one about you later, actually. Yes.

Lotz: You can [unclear]. I was on the board of the Rodeo de Santa Fe. In amateur rodeo, I did a number of speed events and different things like that with my last horse. Rick and I were very involved in the country Western scene in terms of dancing and things like that. We had more damn fun dancing. He liked to follow and he followed beautifully and I liked to lead and I led well. We would have more damn fun—excuse my language—country Western dancing. That was another gift that he had, musically inclined. He could dance, sing, you name it. A very gifted, a very, very gifted man. There are not that many people like Rick that show up in life. I also wrote down, we socialized together. We had a lot of friends in common. That is going out to dinner. That is the rodeo stuff, different gatherings and groups. We socialized a lot together. We were good friends.

Q: Yes. Someone told me you had nicknames for each other. [Laughter]

Lotz: Well, those were given to us.

Q: Oh, yes?

Lotz: I didn’t take one myself. The one that they gave to Rick was Penny. Yes. Penny. Why they called him Penny, I don’t know. [Laughter] I’m not going to share with you—

Q: You don’t have to share—

Lotz: —what they called me. [Laughter]

Q: Yes, someone told me you had nicknames. I wanted to know what the story was.

Lotz: Well, back in the early seventies, there were some gay men who came over to New Mexico, artists, and they brought with them this whole contemporary gay attitude that I’d never run into before, where they called each other by girls’ names, and occasionally they would get in drag. I’m like, “What is this?” I’m this guy that just got out of the Army. All I had was a motorcycle, lived in a little old adobe out west of town. It’s not about me, but that was about the time that this was going on. A lot was changing. They gave us people names. Whether we liked them or not. [Laughter]

Q: We’ve gotten into this a little bit already. How would you describe Rick? Like you said, he had a lot of relationships with a lot of different people. I imagine your experience of Rick, and how you saw him and how he was with you, was probably very different than how he might have been around other people, depending on what he was doing.

Lotz: Probably. What I wrote down is that we must now remember that he was a very talented artist. He was not an ordinary artist. Where he drew his inspiration from, I don’t know. I observed him always working, always making things. He was incredibly creative, and that was part of who he was, and incredibly talented. I have known a number of people who work in ceramics and ceramic artists, and yes, primarily they did bowls or they did jars or things like that. He took it a step or many steps further than simply that. As you go with the gas cans, there was a whole other body of work that he did that is extraordinary. It was never surprising what he did. He seemed to allow that creative gift that he had to flow through him without even thinking about it that much. How he approached things—it just came out of him. He was not overly intellectual about what he was doing. That was my take on it. It flowed from him so freely.

I wrote down that he was scholastic and he was, he was a very bright man and was very involved in a lot of things scholastically. That’s also who he was. That part of him, I don’t know that I knew that well, because that was involved in his writing, in the different things that he did. I’m trying to [remember] the name of the gallery in New York where he showed and it’s escaped me right now. I know that he showed work around the country. He had many people that he knew that purchased his work. He lived at many levels culturally in society. I knew him simply as the one that we did together. I never tried to push my way into his life in those other areas. He kept that. It’s interesting because he kept all those different lives as they were with those people that he got involved with. He didn’t bring us all together like someone overly codependent would. He kept things in order in an amazing way. He did a very good job of that. What else did I write down?—that he was not in one simple group, but many business and social layers in terms of his life and who he was. I got to see that from afar. Particularly in photographing his work for people who owned it, where I saw things go, exhibits he had. Yes. [Pause] I don’t think I can add anything to that.

Q: You don’t have to [if] you don’t want to.

Lotz: Okay.

Q: What do you remember most vividly about Rick? I feel like we’ve been talking a lot about that, but if anything pops into your mind or if you have something written down—

Lotz: I remember most his lively personality, very engaging. That was it. He was so easy to be with and talk to. He engaged you as you engaged him. He didn’t hold back, he didn’t hide. He was so present in his life. I’m sure you’ll hear that from many people who knew him. He had this amazing personality. He could be quiet [laughter], but by and large, no. He was very engaging. I wrote [about] him, he got his hands dirty. That’s one of the things that I like about all people, all artists who get their hands dirty. Dirt is something that I love and Rick loved dirt. He made art out of dirt. I make adobe out of dirt, building and things like that. He made art of dirt. I don’t know that Rick and I ever talked about this that much, but all life dissolves into dirt. It’s all around us, century upon century upon century of life turns into the dirt we walk on. He was making art out of that clay. It got turned into something extraordinary. There within those walls of that clay is the history of that earth. I thought that was pretty amazing. That would be true for any artist, but he did not have any trouble getting his hands dirty. Yes.

He had a very creative spirit, I wrote down. How did he get that? Because, being a photographer, being an artist, living in Santa Fe for almost fifty-five years, I’ve met an awful lot of artists and I’ve photographed a lot of artists’ work. I want to say some of them have a larger creative sphere than others. I’ll never know why all artists go into the work they do, but they were given a gift, I think upon birth. If they’re willing to look into that gift and allow it to express itself, their art starts to grow and they move into [unclear]. If they’re willing to continue to let that grow, [they can] do amazing things. Obviously not everyone is an artist. But Rick was an artist and he allowed that gift to be expressed and to continue to grow, and not everybody does that. Many artists will get to a point where they’re successful and they’ll do that over and over and over again. Rick was not that way. “Let’s go to the next challenge. Let’s go to the next challenge. Whether it’s successful or not, I’m moving on.” He continued to do the variety of things that he did, but he never got stuck in a place [unclear]. That was one of his greatest gifts. The man was amazing. Is amazing. I also wrote down that he had a large persona [laughter], they would talk about that. “You lead, I’ll follow.” [Laughter] “Oh, I’d like you to meet so-and-so. Oh, I’d like you to meet so-and so.” [At] his gatherings, I’d meet some of the most amazing people that I would not run into in my life, in the real world. They were all there because of Rick.

Q: I heard he was quite the trash-talker too. [Laughter]

Lotz: Funny, I don’t remember that, because I must be a trash-talker as well. [Laughter] But I’ve tried not to.

Q: You’re in New Mexico, that’s part of the culture here. [Laughter] We love trash talk.

Lotz: We do. I don’t know the culture of New Mexico [unclear]. New Mexico is an incredible land. It’s a unique experience to live here, and not everybody loves that, but I totally love it. I love the Hispanic culture and language and, having an Italian mother and living in that Italian culture, I feel very comfortable here. Okay, enough about me.

Q: Oh, you’re fine. You’re fine. You touched a little bit on this, but how did Rick’s personality manifest itself in his artwork and how did you see that also in his scholarly practice, which you had an eye into?

Lotz: Okay. What I wrote down was that he took inspiration from others, but he made it his own. He didn’t steal from others. He allowed himself to be moved by other peoples’ work, and other people, but then it went into Rick and then it came out as Rick’s. He didn’t copy or steal from others. Yes, he was inspired by other artists, historic pottery and historic people. I think history was important to him. But he didn’t steal. He allowed it to come into his persona, into his intellect, into his creativity, but then it came out as Rick’s. That’s wonderful. That’s also amazing. Not everybody does that, because a lot of people steal, but he didn’t do that, in my opinion. That’s a pretty simple answer to your question.

Q: To that end, you’ve talked about Maria Martinez, you’ve talked about his pottery practice in relationship to some of the communities he was close with, so how would you describe Rick’s relationship with the various communities that he existed within?

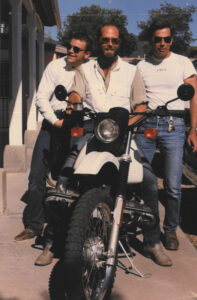

Lotz: I wrote down that he moved in many communities. From clients to his galleries, [pause] he never imparted to me his relationship with those other people and those other communities. Our relationship was our own. He did not bring me into that. I don’t think he did that with his other friends as well. The friendships he had with his friends were theirs. He didn’t try to overlay or underlay those other relationships, either because of their importance, who they were, or for any reason. He did not hold back introducing you to his friends, but it was up to you if you were going to do something with that. I’m talking about codependence, but a lot of people, particularly artists or people who have to work for a living, [can be] very codependent in how they achieve their goals. [Unclear] Rick was never out of balance with that. He kept his own integrity, his own power. Yes, he loved other people, but they didn’t run his life. He was his own man in that sense. I wrote down, he had a large range of friends. Why that was, was because he was so engaging. No matter who the people were that he was involved with, they all [unclear]. In the photograph of him sitting on that motorcycle, there’s a friend named Tom King, who was standing next to us. What did Tom do? He was in the markets, he was a financial guy. I’m not sure why Tom came over to New Mexico, but he did. They developed a great friendship.

Rick eventually did get his own motorcycle, and I was a little cautious about that—I’d always been on a motorcycle [unclear] my whole life—but he wasn’t. He had a Porsche. He had—what else did he have? I don’t remember now. [Laughter] As he became more successful, he had more money. He bought a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. He continued to remodel his home and his studio, and he did a great job with that. His humor, again, his humor was so engaging. I don’t think that any of his friends—or how can I put this? He brought so many people into his life with his humor. We see that, humor is very engaging. It allows you into the heart of others. He had a very open heart, but he also had very good boundaries, about himself and about his work, about his life. One had to appreciate that. At some level, I’m talking to you and I realize, he had a level of maturity that perhaps I didn’t have at that time. How did he have that maturity, I don’t know. But he did. He could do that. Yes. Yes.

Q: Do you have a favorite memory or story about Rick that you would like to share? Obviously, you’re welcome to share more than one.

Lotz: I have a couple of things that I wrote down that I thought about. When I think of Rick—have you ever done country Western dancing?

Q: Been a minute. But yes. It’s been a while. They still do it at the [Santa Fe] Social Club.

Lotz: Social club?

Q: Yes. Yes, they have a country Western dancing night.

Lotz: Okay.

Q: Yes.

Lotz: For anybody who does country Western dancing, your arm’s out, one leading and one following. [Unclear] Rick and I danced, we were—not a couple, well we were a couple, in this movement. He followed so well that we would dance around the floor, with all the other guys in the gay bars and gay rodeos and [unclear] parties, and he was an amazing partner. That’s one of the things we loved about each other.

The other thing that I wrote down was that he had to [unclear] as his life was ending. In 1981, we discovered this virus, called—what did they call it? [Pause] AIDS. HIV-AIDS. No, gay-related immunodeficiency, GRID, they called it GRID. I first became aware of it when a friend of mine from Los Angeles [California] who had [unclear] was concerned about possibly having it, his [unclear]. This was 1981. All of us came in, watched from the early ‘80s until the mid-to-late ‘90s, people—gay men, and others, [unclear] died of AIDS. My ex died in 1990. Rick died in ‘94. I’ve often wondered if he had lived another year, if the medications that were coming out at that point would have allowed his life to go on, because many of the men who lived that long, they got on [unclear] and saved their lives.

As he was approaching the end of his life, he knew it, and there were—I don’t know how many of us there were, maybe three or four of us, friends of his, that he wanted to be with him when he left. His doctor, Dr. Walkins, and I think I should know this, his doctor [unclear]. There were three or four of us who stayed with Rick, by his body, until the morphine stopped his breathing and he passed. We were supposed to clean his body, which we did, we washed his body. We wrapped him in a sheet [unclear] and took him to the crematorium, I can’t remember the name of it now, and they let us put his body into the crematorium. We got to take him from that place at home to the crematorium, and I’ll never forget that. I buried a lot of men in my life, who died [unclear], seventy-eight, seventy-nine years old. That’s one thing that I will never, ever, ever forget, that he allowed us to be with him in that process, and [unclear]. It’s a very, very, very important part of my memory. [Unclear]

Q: Doing okay?

Lotz: Yes, I am.

Q: Wow, wow. Is there anything else that you want to add that you’d like us to know about him? Also, who is in the photo again, for the record? He brought us a snapshot and it’s a photo of three young men in white T-shirts and blue jeans and—how [do] we call those— and loafers.

[Unclear from 00:37:03 to 00:41:32]

Q: Part of his estate was given to the museum. I don’t know exactly how that happened. I’ve been friends with all the museum directors since the early ‘70s. I don’t know how this happened, but I’m so grateful that it did happen. So that all the [unclear] didn’t get thrown all over the country. His artwork is all over the country, there’s a collection that got put together, came to the museum, that’s extraordinary. It’s extraordinary that you’re doing this exhibit. From what you have shown me so far, how you’re doing it—I don’t know want to say it’s profound, but it is. It allows you to see what this man was doing, how he was doing it and making this work. [Unclear]

Q: Thank you. Yes, it’s been quite a journey.

Lotz: I would think so.

Q: Fascination with uncovering these different parts of Rick, and understanding him as a person, not just as an artist, but he was, right? Like you said, he planned the estate, but Juliet Myers, his assistant, executed it. I have yet to speak with Juliet. Truthfully, I am a little bit apprehensive—

Lotz: Really?

Q: —to approach Juliet. Because she was also with him in his final moments and I can tell that it’s very close. My desire to be respectful is turning into anxiety [laughs]. I know it’s no big deal, but at the same time…

Lotz: They were very close and very intimate. She was his assistant, she worked for him and was with him so often—

Q: All the time.

Lotz: All the time in his studio. She’s got a lot of information. I would very much have her speak to you, only because—I love Juliet, we met in 1984, when she would go over here, and she is actually my assistant, [unclear]. She has a very good mind, and I would not be intimated at all. She’s very loving. I think get your [unclear]. I’ve also got to mention, something I’ve [unclear], is I don’t think Rick every wore shorts.

Q: Yes? No shorts? [Laughs] No shorts ever.

Lotz: No shorts ever.

Q: Even when he was out in the mud and collecting cow pies?

Lotz: Oh, no.

Q: Probably not. Thinking about me being in the rigor of the [unclear].

Lotz: I’m also thinking, he got back [unclear], where you wear no shorts.

Q: Unless they were running or playing basketball.

Lotz: Things like that. Where I was raised, my father said, “After fifty, you’ll wear no shorts.” That’s not the case now. You wait until they’re fifty, they start wearing shorts.

Q: No one can tell you anything. [Laughs]

Lotz: We’re drifting. [Laughter]

Q: Or we’ve achieved something, who knows. [Laughs]

Lotz: But I would definitely spend time with Juliet and let her open up about Rick. Because there’s a lot of information. Please don’t be intimated.

Q: I’m mostly not intimated, I think I’m—

Lotz: You got a lot. If anyone should be intimated, it should be Juliet.

Q: I’ll come over here, cracking jokes about Gladys Kravitz on TV. [Laughs] No one will have anything to worry about with me. If you feel like we’ve reached the end of your memory mine, and if you’re feeling—is your mouth tired?

Lotz: No, my mouth has been tired out—

Q: That’s good.

Lotz: —talking with God. I’m trying to think of anything more about his spirit and who he was, and I think maybe I’ve shared all that’s going to come forward. Unless we continue to talk about everyday things. He died in ‘94. That’s thirty years ago. I’m very lucky to have a lot of friends, so I haven’t thought much about Rick on an ongoing basis, other than it’s sad we lost him. Because he was an amazing human being and artist. I love that you’re doing his exhibit, honoring him. It’s very cool. Very cool.

Q: Thank you. I’m excited. October 6th!

Lotz: Yes.

Q: October 6th, 2023, the show opens. It is 2:42 p.m., and we will conclude the interview at this time.

[END OF INTERVIEW]